Originally published March 18, 1994, in Comics Buyer’s Guide #1061

Originally published March 18, 1994, in Comics Buyer’s Guide #1061

Maybe once a year or so, I indulge in a column that’s mostly self-promotion. So here’s your warning that the following is largely a commercial announcement. If you want, you can skip past it to another section that starts “Now this is interesting…”

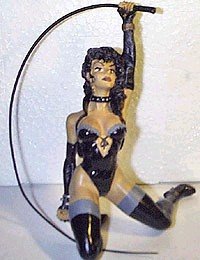

When George Perez and I were first embarking on Sachs & Violens, we would be attending conventions and eyeing covetously the sort of statues produced by Randy Bowen Designs and thinking, “Wouldn’t it be really cool if there were a J.J. Sachs statue?” (J.J. being our whip-cracking, lip-smacking heroine).

Eventually, with the help of colorist John Stracuzzi, we hooked up with Randy himself and worked out the details. For Randy, producer of such pieces as the Sandman, Death and Doc Savage statues, it would be a pleasant change of pace since there would be no convoluted legal and approval system for him to go through. In this case, every step of the way needed the okay from exactly one guy: George, since he had final say over all artistic matters relating to Sachs and Violens. George worked closely with Randy and his diligent art team because—since this was the first 3-D rendering of any Perez-drawn character—he wanted to make sure it was done right.

And she was done right. Everything, from the angle of her nose, to her spikes, to the high cut of her costume, to her poseable whip (yes, you fetishists you, she comes with a poseable whip) is dead-on accurate.

Since we were embarking on this project purely because we thought it would be a cool thing to do, we decided to keep the price as low as possible. After all, we hadn’t conceived the project as a mass-market, high-ticket, big profit item; we wanted to do a neat little collectible that fans of the series, and of George’s work (or our work together on the title) could get their hands on.

First thing we did was limit the production run to a strict 500 pieces. That’s all, forever, finished. When we say “limited edition,” we don’t mean “limited to whatever we can sell.” We mean “limited,” and 500 was the minimum number we could produce where the per unit cost was feasible. (Unit cost was a concern, after all, since every dime involved in making the statue was coming out of mine and George’s pockets.)

Second thing we did was look at the prices of other such items: $125-$150 and up, for statues being produced in far greater numbers. Then we figured out how low we could price the statue and still make back the money we invested, plus cover any additional costs we hadn’t anticipated (plus produce a limited edition print of George Perez’s rendering of the J.J. statue to accompany the piece). What we came up with: $85, plus $5 for shipping and handling (via UPS, mind you. Since there’s only 500 of them, we don’t want any going astray and being untraceable.) Third thing was that we decided not to solicit them through the standard catalogues and direct market avenues. (J.J. Sachs being accused of soliciting! Horrors!) The reason for this was two-fold: First, if we got orders for more than 500, then we’d have to start allocating or shorting people. And second, we’d have had to kick the price up by about 40% in order to accommodate the discount we’d be providing the distributors. Get it? You’d have to pay more, and we’d make the same amount of money, so that the retailers and distributors could make their profit on something that we really weren’t doing for profit. Now if we do wind up making money off it, we’ll be happy. But it won’t be a lot.

A prototype of the fully painted statue (she’s not holding the poseable whip—some things are being left to your imagination for the moment) is pictured on this page. Believe me, the picture doesn’t do her justice. She doesn’t have a base because she crouches perfectly well on her own, making it easy to display her anywhere you want. Hëll, you could even mount her on your dashboard… so to speak.

(Editor’s note: I’ve removed the information for ordering the statue, since the offer has long since expired. And the picture on this page is of the actual statue, not the prototype mentioned above, as I found a color picture to use here.)

By the way, for those who are wondering when the series will be continuing: Have no fear. Our act is solidly together. Issue #2 has, in fact, been done since November–there just wasn’t time to get it out during the sales period. But it will be coming out in March, followed by #3 (which is almost done) in April and #4 (which is well under way) in May. In the meantime, the cardset from Comic Images (which features the entire story of #1 and #2, plus all-new card copy written by me for every card in the set) is doing respectably. It’s been an exciting project for George and myself since we’ve never had the opportunity to do this sort of creator-owned venture before. Plus there’s been inquiries from Hollywood-types, so… you never know.

* * *

Now this is interesting…

In the latest New York Times, an attorney (at least, I’m presuming it’s an attorney) places an interesting coda to the entire Tonya Harding business. Many people (including myself) have been contending that she’s innocent until proven guilty under our legal system.

Turns out she’s not.

“The presumption of innocence,” says letter writer Bernard T. Raizner, “is not part of the United States Constitution nor the Bill of Rights.” Raizner goes on to say, “Even in criminal proceedings, the presumption of innocence is not a rule of law, but a rule of evidence–and the distinction between the two is this: A rule of evidence is only applicable once a trial begins—it’s a principle the jury… must apply in making a decision. However, before trial it is not a rule of law that our judges are supposed to follow.

“The proof of this lies in the fact that our jails are filled with men and women who are awaiting trial and cannot afford bail. (They) are incarcerated, although they are merely accused and have not been proven guilty of any crime.” For the purpose of setting bail, “the defendant is presumed guilty!”

To me, this definitely falls under the category of “You learn something new every day.” I mean, I knew about bail basically operating as if someone might be guilty. I’d just chalked that up to the same notion as the First Amendment providing protections for free speech, but only up to a point—stopping short of shouting “Fire” in a crowded theater, or other potential threats to public safety. But I didn’t realize that there was genuinely no constitutional assurances.

Gee.

Maybe there should be.

I mean, I always thought that was one of the most laudable aspects of our society… the “innocent until proven guilty” thing.

It’s somewhat dismaying to learn that, legally, there’s no reason to presume that someone isn’t automatically guilty of every scummy thing of which they’re accused. It seemed… civilized, somehow.

This is just another dismaying truth about our legal system brought to my attention within recent months. Frankly, it’s starting to get pretty dámņëd depressing.

(Peter David, writer of stuff, can’t help but remember the column he wrote a couple years back about heroes. About how it seemed that we had fewer and fewer heroes left to us, and one of the very few sources remaining was the Olympics that brought us shining, glowing heroes every couple of years, who then graciously vanished from the spotlight before terrible and disheartening things could be brought to light–which is what seems to happen with heroic figures in every other walk of life. Some people claimed that column was unduly harsh. Yet not only do we now have the Kerrigan/Harding business, but other stories are surfacing featuring cut-throat competition. One figure skater, for example, described how several years ago a competitor at the Olympics almost ran her over. Thus do we, as a society, die a little bit more.)

Still proudly display my JJ statue. Unfortunately, the whip has not survived several moves…the vinyl portion is lost, and the sculpted handle has broken off. 🙁

.

–Daryl

I don’t think the accused should be assumed innocent until proven guilty in all absolute permutations. That is strictly for purposes of the jury, and for whether the accused will permanently have their rights revoked/be imprisoned. If we take innocence until proven guilt as an absolute, then, for example, the legal system would not be able to make a distinction between those persons at arraignment who could safely be released on their own recognizance between the time of their arraignment and their trial, and those who could not, which would be perverse. (“Sorry, Madam Prosecutor, but as the presiding judge in this case, we can’t deny bail to Mr. Damien Kindbumser, even though they found him in the process of raping a ten-year-old girl in his basement, with seven other kidnapped kids chained to the walls and gagged, and caught the entire thing on tape, is because he’s presumed innocent until proven guilty. So tell him to pick up his chainsaw and get outta here, and make sure he shows up on January 29 for trial.”)

.

Another example is that it would mean that the public cannot form their own good faith conclusions based on the evidence and reason, including in cases in which they feel the system has failed, as when an innocent person is convicted, or a guilty person is found not guilty. This means I cannot form a conclusion on O.J. Simpson or Lizzie Borden, and act on that conclusion in an applicable situation, because well, they were both found not guilty (at least in the case of Simpson, at his criminal trial). But obviously, this is inane.

.

Former L.A. prosecutor Vince Bugliosi goes into this in his 1996 book, Outrage (Pages 29-30):

.

Contrary to common belief, the presumption of innocence applies only inside a courtroom. It has no applicability elsewhere, although the media do not seem to be aware of this. Even the editorial sections of major American newspapers frequently express the view, in reference to a pending case, that “we”—meaning the editors and their readers—have to presume that so-and-so is innocent. To illustrate the presumption does not apply outside the courtroom, let’s say an employer has evidence that an employee has committed theft. If the employer had to presume the person were innocent, he obviously couldn’t fire the employee or do anything at all. But of course he can not only fire or demote the employee, he can report him to the authorities.

.

Actually, even in court there are problems with the presumption of innocence. The presumption of innocence, we all know, is a hallowed doctrine that separates us from repressive regimes. It’s the foundation, in fact, for the rule that is the bedrock of our system of justice—that a defendant can be convicted of a crime only if his guilt has been proved beyond a reasonable doubt. However, legal presumptions are based on the rationale of probability. Under certain situations, experience has shown that when fact “A” is present, the presence of “B” should be presumed to exist unless and until an adverse party disproves it. For example, a letter correctly addressed and properly mailed is presumed to have been received in the ordinary course of mail delivery. But when we apply this underlying basis of probability for a legal presumption to the presumption of innocence, the presumption, it would seem, should fall. Conviction rates show that it is ridiculous to presume that when the average defendant is arrested, charged with a crime, and brought to trial, he is usually innocent. But obviously, the converse presumption that a defendant is presumed to be guilty would be far worse and, indeed, intolerable. Our system, for readily apparent reasons, is far superior to those in nations, mostly totalitarian, which presume an arrested person is guilty and place the burden on the accused to prove his innocence.

.

The solution would seem to be simply to eliminate the presumption-of-innocence instruction to the jury, keeping those two necessary corollaries of the presumption which do have enormous merit: first, the fact that the defendant has been arrested for and charged with a crime is no evidence of his guilt and should not be used against him; and second and more important, under our system of justice the prosecution has the burden of proving guilt. The defendant has no burden to prove his innocence. It is one thing to say that the defendant does not have to prove his innocence, and that in the absence of affirmative proof of guilt he is entitled to a not-guilty verdict even if he presented no evidence of his innocence at all. To go a step further, however, and say that he is legally presumed to be innocent when he has just been brought to court in handcuffs or with a deputy sheriff at his side seems to be hollow rhetoric. One day a defendant is going to stand up in court and tell the judge, “Your Honor, if I am legally presumed to be innocent, why have I been arrested for this crime, why has a criminal complaint been filed against me, and why am I now here in court being tried?”

Contrary to common belief, the presumption of innocence applies only inside a courtroom. It has no applicability elsewhere, although the media do not seem to be aware of this. Even the editorial sections of major American newspapers frequently express the view, in reference to a pending case

Ðámņ that dangling repeat paragraph at the bottom. Ðámņ the lack of a Preview function.

Don’t be upset. I wasn’t gonna read it anyway…

.

PAD

Ouch.

The thing is, the phrase, “innocent until proven guilty,” doesn’t hinge on the word “innocent” (as some people believe) but on the word, “proven.”

.

It is like how people complain how expensive things are in our “free society.” It isn’t that kind of “free.”

.

The phrase doesn’t mean to let the suspect go as if he were innocent. The phrase means that the burden of proof is on the accuser, not the defender.

.

Without this, a person sitting at home alone watching TV could be conviced of a crime with no hard evidence, but simply because he has no way of proving that he did not do the crime.

.

And, again, this is just instruction to the judge and jury. The police assume that a suspect is guilty, and collect evidence to prove otherwise. This way they can eliminate suspects as more evidence is uncovered. If they assumed the suspect was innocent, there would be no need to continue investigating.

.

Could it be phrased better? Maybe. For the nit-pickers and rules-lawyers (gaming term to mean someone who splits hairs and definitions of words to alter the intended meaning of a phrase to fit their premise)? Certainly.

.

Does it work? I think it does.

.

Theno

Merely as a technicality, the only TRULY “free society” would be one of pure anarchy, since all “free” societies operate under a strict (often very stringent) code of laws.

And if you’ve read Larry Niven’s story “Cloak of Anarchy”, you can get an idea of how a totally lawless society can go sour really quick.

On the other subject, Peter, I found a JJ statue on an auction site, no idea of the price. She looked to be in perfect shape, and the whip was intact. I whimpered…